Table of Contents

Committing to Our Future

The Foundation for Tacoma Students’ platform lays out a comprehensive set of policies and investments that respond to the educational impacts of COVID-19 and invest in the future of our youth. This platform aims to ensure that all students across our PreK-12 and postsecondary systems are on the path to achieving success in school, career, and life.

In the near term, focusing on learning acceleration for the 2022-23 and 2023-24 school years will help our students recover academically from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Investments at the State level to build a great workforce of principals and teachers, and provide free access to advanced coursework for all students will help to build a PreK through 12th grade system that provides an exceptional learning environment, and gives students a jump start on their post high-school plans. Lastly, free school breakfast and lunch will provide for a universal basic need and nurture overall student health and well-being.

Beyond 2023 and 2024, fundamental changes to Washington’s school funding model will address the need for increased funding overall and the structure of how we raise and distribute funding, bringing true equity into the system. Additionally, guaranteeing students the support they need to complete the FAFSA or WASFA, plus the provision of free community or technical college, ensures that every high school graduate will be on the path to a postsecondary credential or good-earning wage job.

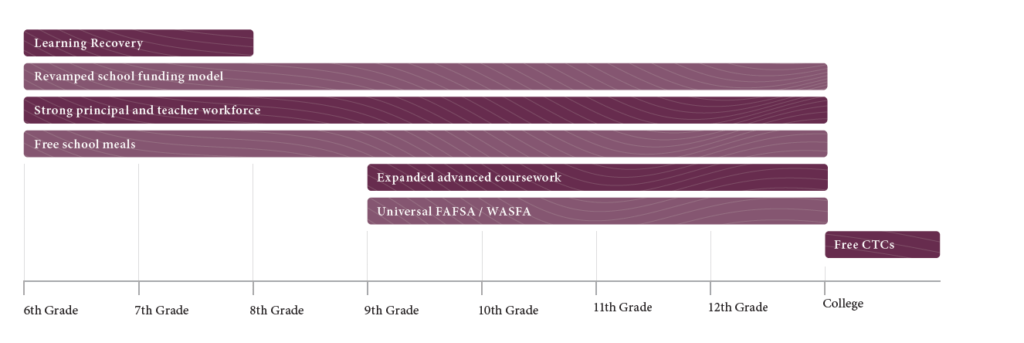

Here is how a a sixth-grade student would benefit from these policies through the course of their school career:

Near Term State & Local Level

Utilize federal Learning Loss Recovery funds to invest in effective interventions and strategies to accelerate learning recovery.

Two and a half years after the pandemic, it’s more apparent than ever that COVID’s disruption had punishing consequences for student learning. State and national testing data show worrisome math and reading achievement declines between 2019 and 2022. The declines were broad-based — affecting students in every district and all demographic groups.

While the state-level Smarter Balanced Assessment shows evidence of academic recovery between the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years, the learning lost to the pandemic will not be easily restored. Where the financial capacity exists, OSPI and school districts should work together to explore the potential for utilizing federal ESSER funds for the following interventions:

Targeted Intensive Tutoring

A robust body of research and evidence lays out the best approaches for targeted intensive tutoring. Districts and school leaders should think of tutoring as existing on a spectrum. Even if resource constraints make the most effective version of intensive tutoring not feasible, there are still a lot of benefits to students to incorporate just one or a few of the most effective approaches.

Expanded Learning Time

Research on expanded learning time shows that when evidence-based methods which maximize teaching and learning are deployed, the extra instructional time helps students catch up academically. The City of Boston offers a good example of a summer learning program that maximized the amount of instructional time available to students.

Improved Data Systems

We should have better information about what kinds of investments are working and which are ineffective. To facilitate this, we should have data systems to answer the “what works?” question. Examples of worthwhile data investments include:

- The Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction could report state test scores in terms of standard deviations or lost instructional time. OSPI could also track and report on the correlation between “how” individual districts spend learning loss recovery dollars and measures of student performance to see whether schools are making gains and for which kids.

- Districts could be given the tools to gauge the losses in the various units — like weeks of instruction — that could be compared to the size of different interventions.

More Ambitious Approaches

Free breakfast and lunch for all students, regardless of household income status.

Free breakfast and lunch for all students, regardless of household income status, is a low-cost, high-impact policy. Many researchers have shown that universal school meals improve academic performance among a student body. Research has also shown that universal free school meals reduce suspension rates, and household spending on groceries, improve dietary quality at home, and reduce grocery store prices throughout a local area.

The research bolsters the case for extending universal free school meals to every school district in Washington. This would help middle-class families not eligible for the free school meal benefit and help low-income families who may qualify for free school meals but miss out due to cumbersome income verification processes. There is also a compelling argument that universal free school meals would reduce stigma by letting everyone receive school meals as equals.

Develop, support, and retain great school principals and leaders; and invest in high-quality teacher recruitment, preparation, and retention programs.

At the state and local levels, we should continue efforts to recruit principals and teachers into the profession and create a more robust and diverse educator workforce in Washington. In particular, we should pursue policy opportunities that will bring more teachers of color into the field. This is especially important for schools and districts that serve a higher percentage of students of color, as these students benefit from having teachers who share their racial identity. Recruitment efforts should be coupled with support and learning opportunities for school leaders and teachers, focusing on educators of color to help avoid the negative consequences of high turnover rates.

Principals and school leaders influence overall school culture, and it has been shown that teacher satisfaction with school leaders is key to teacher retention. There are numerous policy opportunities at the state level that could help to develop, support, and retain great school leaders:

- Strengthen principal preparation and set standards to help principals build the necessary skills to improve outcomes for historically underserved students.

- Create a competitive grant program in which high-need school districts receive funding to test innovative strategies focused on building principal pipelines, preparing and supporting principals, creating incentives to recruit strong leaders, and other approaches.

- Invest in principal professional development, mentoring, and executive coaching.

- Research shows that school leaders of color are more likely to recruit and retain teachers of color. Given this, policy efforts focused on principal recruitment and retention should be designed to develop and support leaders of color specifically.

When recruiting and retaining teachers, state leaders should investigate ways to pay teachers more to work in high-need districts and schools or to incentivize credentialing in high-need subject areas. Other policy opportunities include:

- Invest in a well-supported pre-service program for beginning teachers, which has been shown to be an effective strategy for improving the skills and retention of beginning teachers. These “grow your own” programs have also been shown to strengthen workforce diversity and enable districts to address broader staffing challenges.

- Offer continuing opportunities for mentorship, support, and professional learning beyond the first few years of a teacher’s career.

- Create a competitive grant program for schools or districts to create new opportunities for teacher leadership in high-need schools and teachers of color.

- At the State level, we should explore policies that would help high-need school districts that struggle to attract strong teachers. State policy could support high-need districts to finalize their budgets and internal transfer processes earlier and prioritize hiring in high-need schools before filling other vacancies.

- Implement more holistic teacher layoff policies that take into consideration teacher seniority, as well as performance and other school-specific needs. This would help to guard against districts and schools with higher percentages of novice teachers experiencing a disproportionate teacher turnover in hard economic times.

Invest in expanded and equitable access to advanced coursework opportunities in high school that provide the opportunity to earn postsecondary credit.

Introducing students to advanced coursework in high school can help them navigate choices after graduation. Of course, one size does not fit all, but these “advanced coursework” programs provide the opportunity to earn college credit while in High School. This blurring of the boundaries between high school and postsecondary education has been shown to have broad benefits. Areas for policy change include:

- Increased funding at the state level that guarantees a minimum level of access for all Washington students.

- Remove any financial costs that students and their families have to incur to participate in advanced coursework.

- Adopting additional measures to determine student eligibility, such as regular high school attendance, near-proficient writing demonstrations, overall GPA improvement over time, or nomination from a teacher.

- Nurture more articulation agreements between High Schools and Community and Technical Colleges for dual credit CTE courses.

- Continue to build coordination and partnerships at the state level through state law or the creation of forums that bring together leaders from state agencies and local programs.

- Invest in data collection and reporting requirements for dual enrollment access and success that are clearly defined.

Beyond Near-Term State & Local Level

Revise key aspects of Washington’s prototypical school funding model to fund schools equitably, based on the needs of students.

In 2018 the state Legislature made significant changes to how schools are funded, following the state Supreme Court ruling in the “McCleary” case that Washington had not been meeting its paramount duty for decades to fully fund basic education. The changes implemented by the State Legislature did result in an overall increase in state funding to education and made significant progress towards leveling out funding disparities between school districts. This was real progress, but the work should continue. Unfortunately, our current state funding system is still structured in a way that perpetuates funding inequities. We should rewrite key aspects of our school funding systems to ensure that they align with our values and goals for all Washington students.

There are three key opportunities for building a more equitable school funding policy that we believe should be adopted:

Rewrite our prototypical school funding model to no longer be resource-based and instead adopt a weighted, student-based formula.

The formula should begin with a base amount that meaningfully reflects the costs of educating a single student and is uniform statewide.

Change the way we meet the needs of students from low-income families, English language learners, and students with disabilities.

The base formula amount should have simple and generous weighting applied for every student that is from a low-income family, an English language learner, or has a disability.

Levy a designated education tax—a state property tax, the proceeds of which are collected in a state education fund that is used to fund all districts and preserve local discretion in spending.

This full pooling of education dollars at the state level cuts the tie between funding amounts and local wealth levels, providing for funding equity without complicated systems for transferring local dollars between districts.

Full state pooling of education dollars can mean something other than state-dictated spending levels. Instead, districts’ spending decisions should determine the state education tax rate paid by their residents. For instance, there should be a base education tax rate, and every district spending at their formula amount would have its residents pay only the base rate into the state education fund. Districts spending above their formula amounts would see their residents pay a state education tax higher than the base rate in proportion to the degree by which the spending levels exceed the formula amount.

Adopt a universal FAFSA/WASFA completion policy with robust counseling and advising support.

Washington is not alone in our challenges with low FAFSA completion rates, and an emerging policy strategy to address this is to adopt a universal FAFSA completion policy. This means completing of the FAFSA or the WASFA form a requirement for high school graduation. Many states have taken this step, and early evidence suggests it is an effective policy intervention. Louisiana was the first state to enact a FAFSA completion graduation requirement. They have seen notable increases in their FAFSA filing rates, high school graduation numbers, and postsecondary enrollment. The state has also seen the historical gaps in completion rates between high-income and low-income schools evaporate.

However, recent research shows that robust student support, family outreach, and state coordination must accompany a policy of universal FAFSA completion. A policy making FAFSA or WASFA completion a graduation requirement without investing in implementation details and building flexibility would be insufficient.

Key policy considerations include:

- Provide substantial state investment and coordination

- Provide clear outreach to families

- Provide a simple opt-out process that prioritizes privacy

- Support English Language Learner students and their families

- Create incentives for schools to strive for strong FAFSA completion rates.

- Ensure students are supported through completion and verification.

Create an expansive College Promise Program that covers 100% of tuition for all students, plus non-tuition expenses and support services for the most disadvantaged students.

College Promise programs promote student access and success in postsecondary education by reducing the cost of college. Most Promise programs do this by covering up to 100 percent of tuition and fees at postsecondary institutions located within a Promise community. A Promise program, at either the state or local level, has the potential to boost postsecondary enrollment and completion rates. But the details of the program design matter a lot, and a Promise program should include the following design characteristics if it is to be a robust investment:

- Eligibility criteria should be limited to only residency requirements and not include additional criteria such as GPA or attendance.

- Structure the program with a first-dollar model to protect other sources of financial aid for non-tuition expenses.

- In addition to tuition, offer robust counseling, support services, educational interventions, incentives, or stipends.