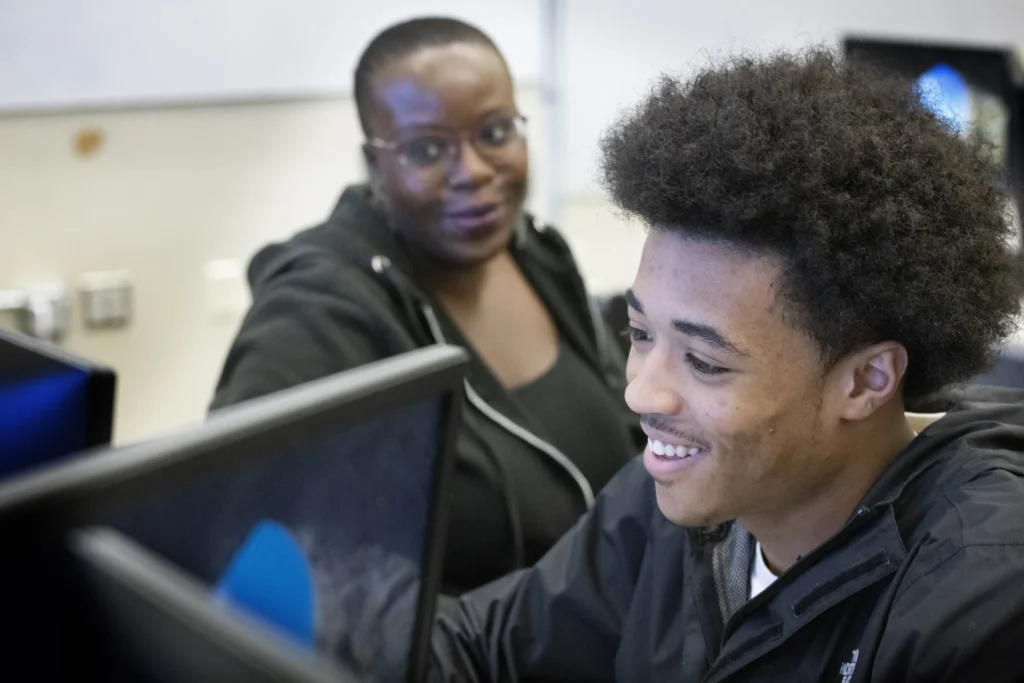

Kai Lewis, right, checks out a financial aid application with the help of Trinity Covington, an outreach specialist with Seattle Promise, during a financial aid application workshop for FAFSA and WASFA (Washington Application for State Financial Aid) submissions for seniors at Cleveland High School in Seattle on Jan. 25. Lewis plans to attend the culinary school at Seattle Central College. (Ellen M. Banner / The Seattle Times)

By Janelle Retka

Special to The Seattle Times

NEW HAVEN, Conn. — For years, Washington has been one of the worst states in the country when it comes to getting high school seniors to fill out federal financial aid paperwork — paperwork that, when completed, makes it much more likely that a student will go on to college.

In contrast, Connecticut, Louisiana and Tennessee lead the nation in getting kids to fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, the paperwork that unlocks the door to millions of dollars in federal and state college grants that do not need to be repaid.

Could Washington learn something from those high-achieving states?

One day in mid-December, three staffers from New Britain High School in New Haven, Conn., huddled in a conference room and imagined a video montage of graduates explaining how grants and loans had helped them attend college.

They plotted house calls to parents, led by staff who spoke their home language. They rehearsed explanations about the benefit of applying for federal aid money and answering questions. And they planned flyers about the FAFSA in English, Spanish, Arabic and possibly more: “Fill it out!! Get money for college.”

New Britain was one of seven Connecticut high schools participating in a state-led workshop to increase the number of seniors filling out the paperwork by 5% compared with the year before. They’re part of the state-led Connecticut FAFSA Challenge, a campaign among schools with a high number of low-income families to support FAFSA completion.

Here’s why the FAFSA is so important: It unlocks federal and state grants and loans for university, community college and technical programs. Students who complete it are 84% more likely to enroll in a postsecondary program the fall after graduation, research from the National College Attainment Network indicates. The rate jumps among low-income students.

In Washington, some districts do better than others. Last year, 79% of Seattle Public Schools seniors finished the FAFSA. Among the standouts: Cleveland High School where in January, students and counselors gathered on a FAFSA completion night to fill out the forms.

Statewide, Washington’s completion rate rose to 41.6% by the end of June, and last year, the state saw a 7% increase in completions, ranking third for year-on-year change. But that’s still well below the mark set by Connecticut, where 65% of students finished the FAFSA form.

State-led programs such as Connecticut’s encouraging financial aid filing are increasingly common across the country, said Bill DeBaun, NCAN’s senior director of data and strategic initiatives. Tennessee poses a similar challenge to all its schools and runs an information campaign to tell students they could attend community and technical college tuition-free for two years if they file. Louisiana is one of a handful of states that have made completing the form (or a state equivalent) a graduation requirement.

Washington does take some of the key steps believed to encourage filing, such as talking about financial aid as early as middle school and offering significant state financial aid that can make community and technical college tuition-free. Last month, a national organization ranked Washington first in the nation for the amount of need-based grant aid it provides per-capita. Since May, over 15,000 school staff and community partners have participated in FAFSA training led by the Washington Student Achievement Council.

So far, state completion data for 2024 hasn’t been released. And nearly two weeks after launching a retooled and greatly simplified FAFSA, the form moved from being periodically available to open 24/7. But kinks continue to be worked out.

The Department of Education recently announced that students’ information wouldn’t be passed onto schools for processing financial aid packages until the first half of March. That’s drawn the ire of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, which worries further delays will ultimately harm students most in need of help.

Data That Guides

Equipped with a FAFSA improvement plan from the state-led workshop in New Haven, New Britain High School’s career specialist Nancy Rodriguez sent out a reminder a week before winter break for seniors to set up an FSA ID needed to file the FAFSA. She also walked two students through the state equivalent of the FAFSA which, as in Washington, provides undocumented students access to state financial aid. Then she attended a FAFSA 101 training.

Weeks later, when the form went live, Rodriguez and her colleagues began rolling out the efforts they plotted during the New Haven workshop. They have 415 graduating seniors to reach, and are aiming to help at least 60% complete the form.

While 54 Connecticut schools are part of the challenge this year, twice that number were eligible to join. Those who participate are offered workshops and training and mini-grants of up to $16,000. New Britain is using its nearly $11,000 for bonuses for staff working directly with students. They’re also using incentives, including student breakfasts and sweatshirts for those who complete the form, and resources such as flyers and events featuring financial aid experts from local colleges.

Connecticut has invested $1.5 million in the challenge since its launch four years ago, and has seen FAFSA filings in the state rise by 10%. Among the Class of 2021, state data shows low-income students were 4.5 times more likely to be enrolled in a college program the fall after graduation if they completed the FAFSA.

A key tool: updating FAFSA completion data for each student daily, so school staff knows who hasn’t filed yet. While Washington has similar data, it’s only updated weekly, said Becky Thompson, director of student financial assistance for WSAC.

Washington has no FAFSA-focused competition setting goals. But its 12th Year Campaign supports schools in providing admissions and financial aid resources to students and families. Over 200 schools participate.

Last year, those schools saw a collective FAFSA completion rate 13% higher than nonparticipating schools, with every racial group outpacing their peers at other schools.

Building A FAFSA Culture

In Michigan, the state offers a certification for school staff to become FAFSA specialists. In Tennessee, any school that raises its FAFSA completion rate year-on-year is lauded as a “champion.” In a single year, 75 claimed the title.

A recent report by local nonprofit Foundation for Tacoma Students recommends steps like this could, collectively, mean more Washington kids going to college.

It also recommends incentivizing schools through grants similar to those offered through the Connecticut FAFSA Challenge, and creating a single website where school officials, students and parents can access all career planning and FAFSA resources — as modeled in Tennessee.

Rather than mandating FAFSA completion, a state equivalent or a waiver, the report suggests making completion part of the High School and Beyond Plan, which charts students’ school and career goals.

Washington should increase its existing work, said Ben Mitchell, one of the report’s authors. That includes pumping up its 12th Year Campaign, and investing more in raising awareness about the Washington College Grant, the state’s most significant financial aid fund, he said.

Still, Washington’s progress shouldn’t be compared to other states, NCAN’s DeBaun warns. Washington is a larger and more diverse state in population and industry, creating a more complex set of needs to meet, he said. It also ranks similarly to several Western states — Alaska, Utah, Idaho and Arizona are the states with lower FAFSA completion last year — that historically struggle with student retention.

Equity In Access

A simple initial step could be setting a statewide goal, said Mitchell. But he echoed Thompson, of WSAC, that the goal is “not about just getting an increased number of forms” completed.

“If the goal is ‘we will increase FAFSA completion by 5%,’ that means every student group increases by 5%,” Mitchell said. If one student group “carries the rest of the population along to achieving the goal” it would undermine the goal.

Tracking FAFSA completion across student races, ethnicities and abilities is something states struggle to do, said DeBaun, since the FAFSA doesn’t ask demographic questions.

Foundation for Tacoma Students suggests Washington’s K-12 schools and colleges band together, creating a database similar to the Washington State Report Card, which would not only illuminate how many kids are completing the FAFSA but also show enrollment and completion in postsecondary programs.

Meanwhile, a proposal from Gov. Jay Inslee’s office suggests automatically awarding Washington College Grants to students who are enrolled in SNAP, or basic food benefits, without an application — a sign to Thompson that the state is exploring ways to improve student aid access.

“Better FAFSA” Begins

This year, more students will be eligible for more money due to revisions to the FAFSA, a project led by U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash. Those changes make the form shorter and allow filers to import their IRS tax filings, eliminating paperwork. But at least for this year, it means students have less time to complete the FAFSA and make sense of their resulting financial aid packages, as the application opened three months after its usual Oct. 1 release.

Despite the glitches with the electronic process, the form is already proving less intimidating, said Najla Jahaf, a member of the New Britain High School FAFSA challenge team who helped two local students complete the form in early January.

“We can tell right away what a big difference it made. It took the students themselves 15 minutes,” she said. “For the parents, I think it took like six minutes. That was it.”

The condensed application period is sure to create challenges this year, however. Ordinarily, half of seniors who submit the FAFSA have done so by this point in the year. That work will now bump against other milestones, like receiving award letters and making sense of them, or choosing where to attend, said DeBaun.

In 2022, eligible Washington seniors left nearly $60 million in Pell Grants, which do not need to be repaid, on the table. With renewed attention on the FAFSA this year, experts hope to see more local policies and incentives to help Washington students better understand and access all the money available to them.

Janelle Retka

This article originally appeared on February 3, 2024 in The Seattle Times by Janelle Retka.